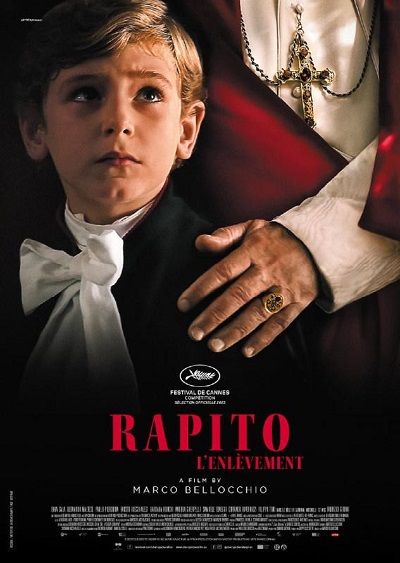

Marco Bellocchio’s “Rapito” – A Reminder of fine Italian Filmmaking

TORONTO – “Rapito” is a film whose scandalous history befitting of a 19th century Vatican, had initially lured the interest of Steven Spielberg. The American Director reportedly dropped the project after failing to find a suitable child actor for the lead role. While screening the film at Cannes last year, Rapito’s Italian Director Marco Bellocchio hypothesized on the American Director’s decision: “My feeling, speculation of course, is that he [Spielberg] may have seen the complexity of this very Italian and dramatic case, for which the Italian language is not necessarily obligatory, but very precious”.

If Bellocchio’s assertion is wrong, his film is certainly no proof of it, as Cannes audiences would later attest by giving the film a thirteen-minute standing ovation, a full four minutes more than they gave Martin Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon”.

The film is set in 1858 Bologna, and tells the true story of seven year old Edgardo Mortara, a Jewish boy, who was secretly baptized by a Catholic maid, and later stripped from his family on order of Papal law – as a Catholic child could only be raised by Catholics. The story of Edgardo’s Papal kidnapping carries historical significance on many fronts as it coincided with and under the rule of the last Pope to reign over the Papal States, Pius IX. He was the Pope who instituted the doctrine of Papal infallibility.

There are countless themes interwoven into this fragile and tumultuous period in Italian, Papal and World history, not least of which is the examination of faith vs. dogma. With Italian unification on the horizon and revolutionary ferment in Europe, Pius’ time as Pope was fraught with pivotal decisions that would set a path forward for modern day Catholics. Edgardo was unfortunately a child victim but also represented some of the consequences for non Catholics resulting from the hegemony of Priestly Rule over the Papal States.

Adding to Bellocchio’s contentions that the story perhaps required an Italian influence, which would undeniably include an eye for detail, the film’s locations could not have transported us better. From the extravagance of the Baroque Church of San Barnaba in the centre of Modena, to piazza Minozzi in Roccabianca, a small village in the province of Parma, Rapito’s locations perfectly evoked Pius’ Italy.

Bellocchio’s cast of actors, a band of performers many other recent American films could easily have employed, remind cineastes that the perceived dearth of Italian actors post Mastroianni/Loren era is somewhat of a myth. With an entire cast worthy of praise, and there were many, it would feel unfair to single any out.

Yet Barbara Ronchi’s portrayal of Edgardo’s grieving and steadfast mother was nothing short of mesmeric. With actresses like Ronchi in existence, how could Michael Mann (Director of Ferrari) in all sincerity not have found an Italian worthy of playing either Laura Ferrari or Lina Lardi?

And so we’ve come full circle to Spielberg’s dilemma of being unable to find the right child actor. It would seem that Spielberg either didn’t have an eye for the actor, or he didn’t look hard enough in Italy.

Bellocchio managed to find three child actors who at times in their performances displayed the gravitas of a seasoned veteran. Enea Sala, playing Edgardo, seems destined to play a role in cinema for years to come. If nothing else, “Rapito” should alert American Casting Directors to talent they would have otherwise sought in Spain.

Massimo Volpe

Massimo Volpe is a filmmaker and freelance writer from Toronto: he writes reviews of Italian films/content on Netflix