Family bonding – time on the rise

[GTranslate]For over a year, many families have been spending more time at home together. We all have Covid-19 to thank for that. To mitigate the spread of the virus, governments have issued widespread lockdowns and implemented stay-at-home orders.

When possible, parents work remotely and children engage in on-line schooling. All this means more time together. But, just how much time do parents spend with their children, the results may be surprising.

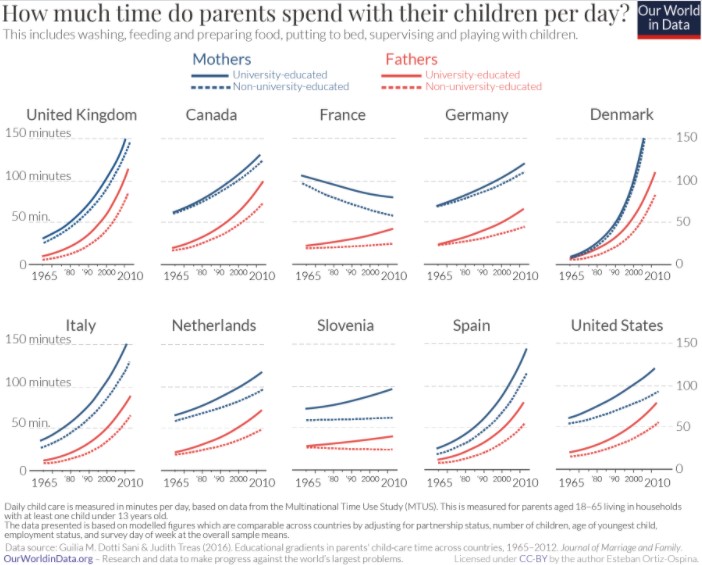

According to Our World in Data, Canadian mothers spend, on average, about 130 minutes per day with their children. For fathers, the average time is about 100 minutes.

In a 24-hour day, with the majority of them spent awake, the amount of time seems rather low. However, Canadian parents spend more time with their children when compared to families in the US. (see graph below)

The graph offers a visual of the data available for select economically advanced and developed countries: the UK, Canada, France, Germany, Denmark, Italy, Netherlands, Slovenia, Spain and the US. One thing that is clear, over the course of 50 years, the time parents spend with their children is on the rise.

Not all families are the same, therefore, the figures may vary. Several factors affect the quality time a parent spends with their children. Hours spend working outside the home, commuting to/from work, family size and structure are some contributing factors as to how much time parents allocate for family bonding.

The data originates from the Multinational Time Use Study which measured the time parents aged 18-65, spend with their children aged 13 and younger between 1965-2012. The bonding time included several activities such as playtime, supervision, bathing, feeding and bedtime routines.

Historically, mothers are the primary caregivers of the family. Therefore, it is no surprise that mothers spend the most amount of time with their children compared to fathers. What also becomes evident, is that the increase over the years applies to both gender roles regardless of educational background.

The only exception appears to be among mothers in France. The amount of time spend with their offspring has declined over the years. In Slovenia, not much has changed among the non-university educated parents. The time they spend with their children has remained fairly constant over the years.

In most cases, parents are spending more time with their children compared to 50 years ago. Several reasons may explain this: economic progress, changes in social conventions and modifications to routine. Perhaps the declining fertility rate among women of child-bearing years factor into the trend. With fewer offspring, one can allocate more time and attention to the ones they do have.

The data also suggest that those who are university-educated are perhaps better positioned to make adjustments to their routines. Parents who allocate more time to interact with their children offer a greater opportunity for childhood development.