Budget proposals may ignore contributor’s financial rights

TORONTO – Like everyone else, I will be watching for details in the upcoming budget; sorry, I meant the “costed” election platform to be presented by the current government. I will be looking for transparency and disregarding rhetoric. No, it will not be driven by partisanship but by purely selfish [legitimate] desires to protect my assets (such as they are) – home and pension.

Let’s leave aside for a moment the equity in homeownership built-up over decades, the equity in pension funds aggregated over the years are every bit a part of the “nest-egg for a rainy day” that all of us have a right to defend. And, I might add, to protect against the incursions by government “easy pickings” taxation measures or incompetence (if not outright fraud) by Plan administrators.

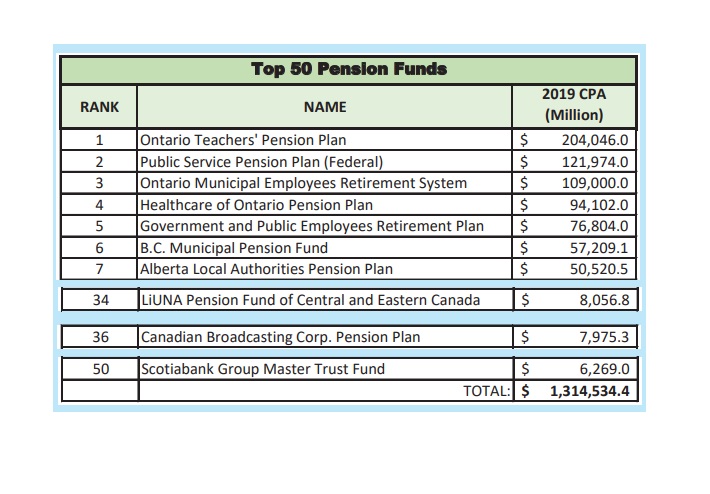

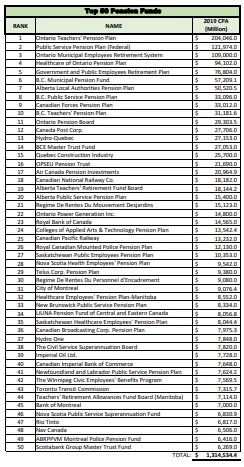

We are talking about Pension Funds with substantial capital whose assets are maintained by (1) the contributions of their members and, (2) the returns on investments earned by the fund administrators. For example, the top 50 pension funds have assets totalling $1.3 Trillion (see charts by Priscilla Pajdo, derived from FSRA, Quarterly Updates 2021), the equivalent of roughly 65% of Canada’s GPD. If we were to add the current value of the Canada Pension Plan – $497 Billion – their combined value would exceed that of the country’s GDP.

Without appearing to be a paranoid conspiracy theorist, with the ballooning national debt and annual budgetary deficit it is not too much of a stretch to appreciate how much of a temptation these funds represent to Finance Ministers – or indeed to less than meticulously scrupulous and honest administrators – might be. Unfortunately, there is a steady stream of examples, some of them associated with the financial meltdowns of 2008-2009, and later, to a lesser degree, of 2013-14.

All “defined benefit” pension funds require a steady revenue stream (“money in”) to be solvent (viable); in a non expert’s language, to make sure you can meet monetary obligations (“money out”) to pensioners (beneficiaries – primarily “old people” who have already contributed or those in unexpected need). That revenue stream is essentially twofold: contributions and returns on investments.

Looking at the chart, a fund like the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan can rely on about 185,000 well paid (according to some), contributors with relative job security. Of course, it may have to pay significant amounts to retirees (about 145,000 at last count), assuming life’s longevity does not exceed projections covered by returns on investments made by the fund. But, it is a BIG plan with lots of resources to ensure [some] compliance with respect to the minimum required by Regulatory Agencies like the Financial Regulatory Agency of Ontario (FSRAO) and the Canadian Revenue Agency, along with their enforcement arms, the RCMP and the OPP.

Often, the big decisions are made in the most unexpected quarters for reasons that, on the surface, have little to do with the monies a “pensioner” has a right to expect. The infrastructure, bureaucracy, to track potential recipients and heirs cannot be slipshod. It may come as a surprise to young, high rolling investor types that contributors have a right to their money. While Pension Funds are not the classic Bank deposit takers, if PFs do not exercise due diligence or obey the minimal rules, we are up the creek without a paddle.

As an MP and Cabinet Minister, like all my colleagues (some more than others), I was frequently lobbied, especially “around budget time”, by financial institutions – including PFs. Their interests lay in securing as much flexibility in the investment process as they felt they needed to ensure “growth” and maintain solvency. As legislators, we were equally concerned about transparency and the delivery of what those pension Plans contracted, ie., pensions to their beneficiaries. Many of these issues spilled over into immigration policies as companies and Unions, pleading desperate need of workers, began to hire “undocumented workers” – people without status in Canada and consequently subject to removal upon being “discovered”.

The best that MPs were able to ensure the vulnerable was the insertion of the obligation that PFs track their contributors so that their assets would be safeguarded. Alas, if those contributors “became lost” or they were forced outside the country their forced savings/contributions would be lost.

Sound good so far? Five years ago, according to a Human Resources and Skills Development official speaking off the record, there were close one million such individuals, 500,000 in Ontario alone.

One construction Union admitted to having more than 10,000 on its lists. Where are they now and what happened to their contributions?