Household food insecurity is growing in Canada: a research by UofT

TORONTO – Based on data from 55,000 families collected by Statistics Canada’s Canadian Income Survey (CIS) in 2022, the University of Toronto has developed a report – entitled “Household Food Insecurity in Canada” and published on November 19 – from which it emerges that from 2021 to 2022, the prevalence of household food insecurity in the ten provinces increased from 15.9% to 17.8%. In 2022, 2.7 million households, or 6.9 million people, including nearly 1.8 million children under the age of 18, lived in households that had experienced some level of food insecurity in the previous twelve months.

“This increase – explain the authors of the UofT research: Tim Li, Andrée-Anne Fafard St-Germain and Valerie Tarasuk – follows three years of relatively stable levels of household food insecurity from 2019 to 2021 and brings the prevalence to the highest level recorded in Canada’s seventeen-year monitoring history”. And we’re talking about data that don’t include people living on First Nations territories or reserves, who are known to have high vulnerability to food insecurity. Going into specifics, the increase recorded by the UofT amounts to 312,000 more families with food insecurity in 2022 compared to 2021: these are, for the most part, families with children under 18 years of age, homeowners with mortgages.

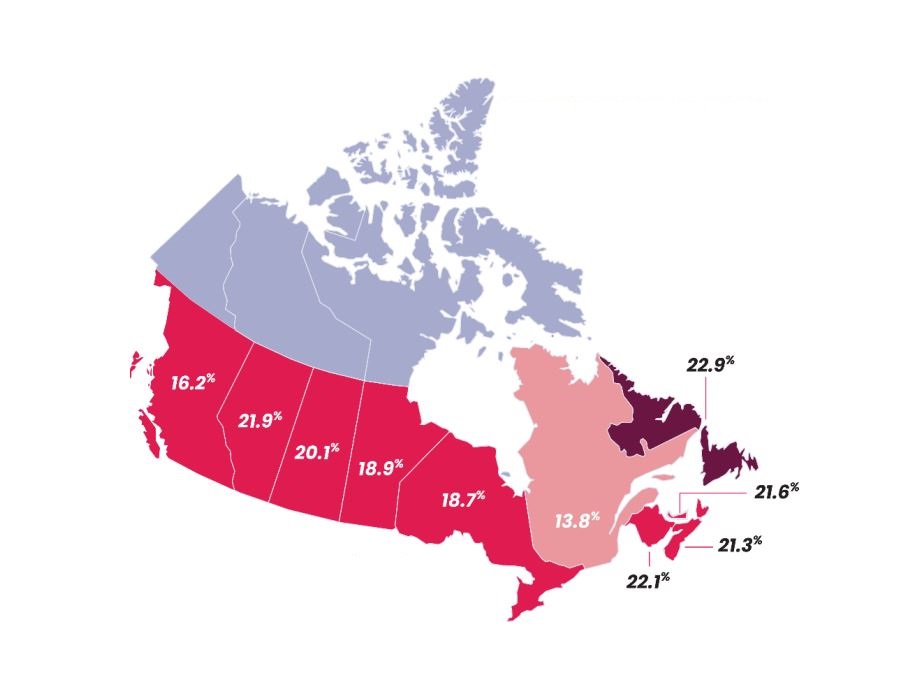

The food insecurity of families varies from province to province. Newfoundland and Labrador had, as of 2022, the highest rate of food insecurity (22.9%), followed by New Brunswick (22.1%) and Alberta (21.9%), while Ontario was at 18.7 %. Quebec had the lowest prevalence of food insecurity in households in 2022, at 13.8%.

Of particular concern is the high prevalence of severe food insecurity in several provinces, including Alberta (7.5%), Saskatchewan (6.5%), Newfoundland and Labrador (6.2%) and Prince Edward Island (6.0 %). The lowest severe food insecurity was recorded in Quebec (2.5%).

“The prevalence of household food insecurity in Canada matters because food insecurity is such a potent social determinant of health” the researchers write, because “people living in food-insecure households are much more likely than others to suffer from chronic physical and mental health problems and infectious and non-communicable diseases. They also have greater needs for health care services, higher rates of hospitalization, and elevated risk of dying prematurely”.

For this reason, according to the researchers, politicians should give priority to reducing food insecurity and implement interventions that target the root causes of household food insecurity. “Reducing food insecurity will require concerted efforts by federal and provincial governments to reconcile income and other financial resources such as assets with the actual cost of living”.

The complete report, which falls within the scope of the “Proof” research project, can be downloaded by clicking here: Household-Food-Insecurity-in-Canada-2022-PROOF

The map above is from the report by UofT